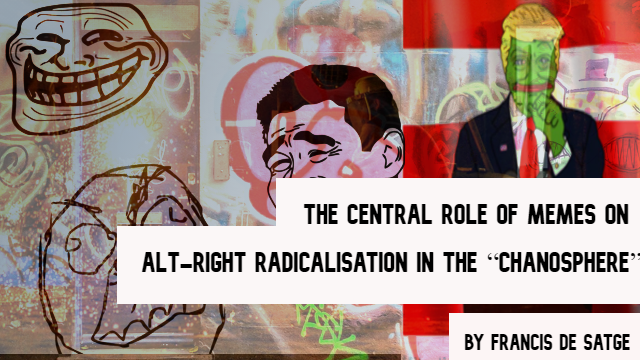

Impact of Memes On Far Right Massacre

Buffalo, NY – On May 5th, before firing upon a group of Black grocery shoppers in Buffalo, NY, the 18-year-old shooter explained his upcoming actions in a Discord chat log, saying, “Honestly, this entire thing is a meme, I’m actually just doing a high-quality shitpost.” Nine days later, he logged onto Twitch and began to live-stream as he gunned down ten people.

While gun reform understandably remains the primary political focus amidst the United State’s climbing number of mass shootings, there’s an influential meme culture that breeds, encourages, and salutes forms of hate, like the kind displayed in Buffalo. And, along with guns, the spread of radical internet propaganda should likewise find space under the lens of massive public scrutiny. Because when the histories of modern mass shooters are unearthed, the paths leading to their ultimate acts of terror are often paved with long trails of time and attention spent in the internet’s darker corners.

In both the Buffalo and Christchurch (New Zealand) shootings, the guns and body armor used by either terrorist were decorated with memes, symbols of white supremacy, and the names of those who previously lashed out in like-minded fits of violence. Similarly, their manifestos and chat logs were dense with content typically found on online image boards like 4chan and 8kun, where they then shared it with followers on open-source message platforms like Discord or Rocket.Chat.

While mass shootings can easily be logged as lonely men acting in solitary bursts of hatred and despair, the psychological conditioning of the modern American terrorist is often more accurately attached to something larger. Many far-right cohorts–from neo-Nazi collectives like Atomwaffen and the Nordic Resistance Movement to alt-right organizations like the Proud Boys or Patriot Front–use and promote the creation of memes as PSYOPs to assist in forming worlds that paint white men as the ultimate victims of Western progress.

The Tools of Chaos

To further understand the influence and evolution of internet memes, Current Affairs Times interviewed Emily Dreyfuss, Senior Fellow at Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy. Dreyfuss has also co-authored the upcoming book, Meme Wars: The Untold Story of the Online Battles Upending Democracy in America (set for release this September), which chronicles how memes have become vital cultural weapons of the far-right.

Dreyfuss explained the investigative methods of her upcoming book and its discovery that the chaos of the digital world often ends up overflowing into the real one: “One of the cornerstones of our research is the fact that these kinds of online communities come together over an idea and launch attacks against other people. And this kind of meme war tends to burst into real-world violence. We argue that January 6th was the result of a meme war and that, in some ways, so is the radicalization of specific white supremacists. Like Dylann Roof, when he found information online that he claimed in his own manifesto turned him into an anti-black racist. That information had been left there as part of a meme war.”

While memes are often considered a URL-age phenomenon, the form is very old. And memes–which are graphic images with superimposed text–have been used in American conflicts since its founding. Dreyfuss explained, “Memes predate the internet. And some of the most influential ideas and symbols in American history, I argue are memes.” She cited the Gadsden flag–the familiar serpent coiled above the text, “Don’t Tread on Me”–as one such example. And of course, the Gadsden flag remains a symbol of libertarian determination to this day and is often found flapping above the scenes of far-right rallies and riots.

But memes have been used to fan the flames of discontent far before the American Revolution. Ever since Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press motioned in the age of mass print, the meme found coveted status as an effective and low-brow template for promoting ideas on a grand scale. The first massive political achievement aided by the printing press was Martin Luther’s viral condemnation of the Catholic church. And while many are familiar with Luther’s 95 Theses, which sparked the long ideological clash between Protestants and Catholics, there was a lesser-known current of Reformation propaganda that consisted of, in part, memes. Much of them targeted Catholic leadership. For example, there’s a known image where the text, “The Origins of the Pope,” is overlaid on a picture of the devil secreting Pope Leo X–and a handful of Catholic cardinals along with him.

One of the most critical elements shared between the Reformation memes of old and memes of the digital age is that the forces used to spread them were, and remain, decentralized. Just as meme creators and shitposters of today operate as passionate individuals and loyal devotees, it was the grassroots converts of Luther’s ideology that energized the creation and distribution of these easy-to-digest images, ballads, and quips flung at the Catholic church. And, as anyone familiar with online chat forums and image boards knows well enough already–when it comes to memes–truth, fact, and balanced discussion take a backseat to rage, obscenity, and singlemindedness.

Becoming the Image

During the interview, Dreyfuss pointed out that many groups of all causes and political leanings use the simplistic power of memes to advance ideas. However, there’s a distinct magnetism and degree to ultra-right-wing usage of memes revealed through how they have consumed the minds of many who end up committing mass shootings.

The matter of Dreyfuss’s book focuses mainly on the advent of political memes and how, in the early 2010s, radical communities began using them to build messaging campaigns around resentment towards minorities, women, and the perceived destruction of the white-male status. “These (online groups) were largely focused on bringing about anti-black and other bigoted and racist sentiments–specifically anti-black and anti-semitic sentiment,” Dreyfuss explained. “And there are a lot of reasons for that. Psychologists, sociologists, and economists can talk about the changing economic position of white males in the US around that time and how much they were threatened by the election of a Black president. And then just a general increase in loneliness in the social media era, where people are meeting up in real life less and going online more.”

Around this time (2011), Anders Breivik, a Norwegian terrorist, posted a 1,500-page manifesto and then killed a total of 77 in the name of preventing a multi-cultural and Muslim takeover of Europe. And eleven years later, Breivik’s name and the names of a handful of other mass murderers appeared written on the gun wielded in the Buffalo shooting.

Along with political resentment, a culture of homage plays an enormous part in how these isolated and seething members of far-right digital communes continue producing a steady pace of mass shootings. Because, as Dreyfuss explained, once murderers commit the act, their tribes often turn them into a meme. Which, for those embedded in such groups, is a status equal to sainthood.

Dreyfuss spoke about how the image of Eliot Roger, another mass killer, was turned into a celebratory reference among the online communities he inhabited, saying, “He (Roger) immediately became a meme and a hero in the Incel group. They watched his videos, quoted them, and turned him into clips and reaction gifs. They refer to him as the ‘Supreme Gentleman,’ which was the way he had referred to himself.”

The Effects of Mass Media

One of the final elements of meme culture’s continued persistence is how violent perpetrators are not only incentivized by fringe-media fame but through the additional incentive of mass media attention.

“In a lot of ways, a meme war and a political, ideological culture war is a kind of a media cycle,” Dreyfuss explained. “It’s dependent on amplification, and it’s dependent on virality…And so in a lot of ways, we have to remember that part of the reason why the violence occurs is that the violence begets media.”

The dependable draw of mass media to mass shootings is an enormous concern. Especially as studies continue to show how copycat crimes consistently arise in the aftermath of horrific terrorism and that many such crimes are linked to a lust for fame. However, the effects operate on a two-way street. Because while the torch of mass media might act as a perverse beacon, it can also spark awareness to fuel the fires of widespread and lasting change. Like it did with the anti-trust laws of the early 20th century, the civil rights activism and anti-war movements of the 50s, 60s, and 70s, and the police reform protests following the murders of Michael Brown and Geoge Floyd. And how, currently, it’s being leveraged in the bitter fight to make sure that those who have had their lives and fates determined by the horror of mass shootings might, at the very least, be made part of the legacy that prevents the next one from unfolding.

Sources:

- Nathan Rizzuti from Current Affairs Times Interviewed Emily Dreyfuss, Senior Fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy

- Buffalo Shooters Weapon Covered in White Supremacist Messaging

- How Christchurch Shooter Used Memes to Spread Hate

- Shitposting, Inspirational Terrorism, and the Christchurch Mosque Massacre

- Accelerationism: the obscure idea inspiring white supremacist killers around the world

- The Use of Propaganda in the Reformation

- The Dangerous Spread of Manifestos

- Does the Media Influence Copycat Shootings?